As a podiatrist dealing with foot mechanics, I am called to treat knee pain all the time. I have learned that there are many ways to help knees and understanding some basic principles can be greatly helpful. When I first joined the practice that I have enjoyed these 33 plus years, it was primarily an orthopedic practice. Most of my patients the first few years were there for knee pain treatment. I was fortunate to have Dr James Garrick, orthopedic surgeon, and Jack Rockwell, physical therapist, to help me develop my skills in treating knee pain. Of course, the patient's feedback on our treatments greatly helped me fine tune the process.

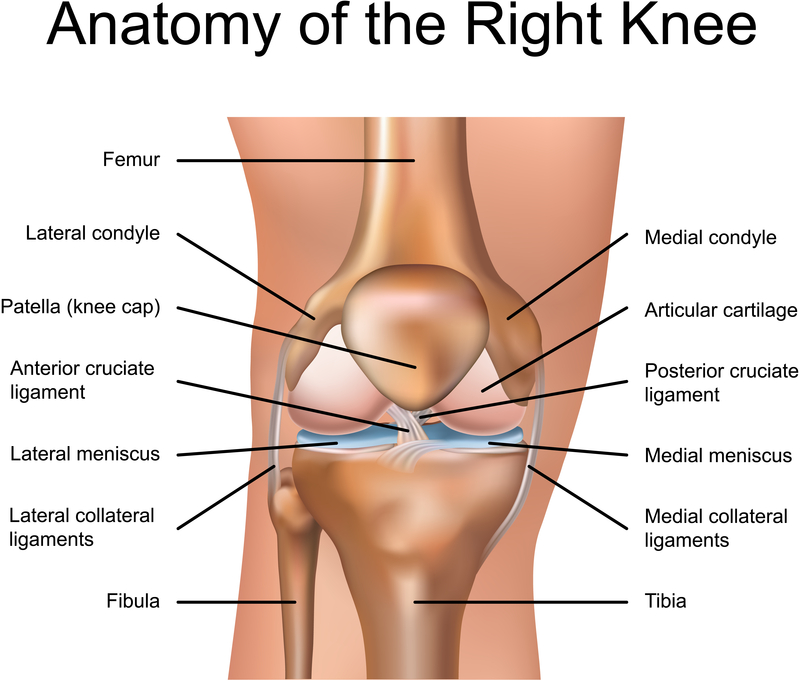

The schema below is meant to just begin to orientate you on knee anatomy. When talking about the knee, you talk about the quadriceps and patella (or kneecap) in front, the hamstrings in back, the "medial" side is closest to the other leg, and the "lateral" side on the outside of the knee. Podiatrists are not called to treat acute knee injuries initially, but need to know the mechanics when called to initiate treatment during the post surgical Restrengthening or Return to Activity phases, or when the surgeon is attempting to avoid surgery in the first place. Shifting weight, stabilizing the knee joint, strengthening the knee, etc, are all in the realm of a podiatrist during visits to help knee mechanics. Podiatrists are called routinely to treat knee injuries that are overuse in nature. This is 98% of knee pain that presents to an orthopedic practice. They are typically non-surgical problems and respond well to many general treatment principles that will be presented here.

The schema below is meant to just begin to orientate you on knee anatomy. When talking about the knee, you talk about the quadriceps and patella (or kneecap) in front, the hamstrings in back, the "medial" side is closest to the other leg, and the "lateral" side on the outside of the knee. Podiatrists are not called to treat acute knee injuries initially, but need to know the mechanics when called to initiate treatment during the post surgical Restrengthening or Return to Activity phases, or when the surgeon is attempting to avoid surgery in the first place. Shifting weight, stabilizing the knee joint, strengthening the knee, etc, are all in the realm of a podiatrist during visits to help knee mechanics. Podiatrists are called routinely to treat knee injuries that are overuse in nature. This is 98% of knee pain that presents to an orthopedic practice. They are typically non-surgical problems and respond well to many general treatment principles that will be presented here.

Podiatrists mainly deal with foot and ankle problems, but the knee is not far behind. This is because the knee is so influenced by changes in foot position from the changes in shoe gear to the design of orthotic devices to the activities they participate in doing. You really can not treat the foot in isolation since “the foot bone is connected to the ankle bone, the ankle bone connected to the leg bone, etc etc”. The knee is influenced by the foot/ankle complex biomechanics, but also by its own independent joint motions, and also influenced from the hip and spine above. Some patients have a one to one relationship between their foot and knee mechanics, and some have a reverse relationship where the foot moves in one direction and the knee another direction. It is crucial to watch your patients walk and run and see what the influence of changes in biomechanics of the foot mean to how the knee moves (you can place the patient in different shoes, different wedges, even different speeds of running). The knee is like the big toe joint in that it is actually two joints in one (“double the pleasure, double the fun”). There is the joint between the femur (above) and the tibia (below), and the joint between the femur and kneecap (aka patella). Problems can occur from one or both joints at the same time. There are so many issues on how the knee cap moves that I can not keep up with all the names for the same problem (patello-femoral dysfunction, runner’s knee, dancer’s knee, biker’s knee, chondromalacia patella, quadriceps insufficiency, etc).

In general, the knee moves with the foot. As someone walks and runs, you want internal rotation at the knee following heel contact (as the foot pronates). This motion is crucial for shock absorption at the foot, ankle, and knee. Then, you want external rotation at the knee from midstance to push off as the foot supinates. These motions, when in sync, produce little or no stress on the knee. But, when the motions are excessive or limited in one area or in opposite directions, trouble occurs. Orthopedists have been studying knee motion for years, along with physical therapists, so they can sense when the motions (or lack of) are problematic. I believe it is really having someone take the time to assess these simple issues to suggest if changing the abnormal stress can help the symptoms. I find gait evaluation to be crucial in this area, not only in the discovery phase, but then in changing the motion to reverse the abnormal stress. I think here lies the problem with knee pain. The physicians and PTs see the abnormal motion, but do not know how to reverse it (sometimes impossible), so surgery is too often gone to.

What are these abnormal stresses that are easily observable in gait?

When we watch someone with knee pain walk and/or run, you look at various aspects of that motion that can produce problems and has cures. Unfortunately, since we are always looking for clues on what we know, sometimes we miss the real problem because we simply do not understand it. All of the following observations can cause problems and can be broken down to various treatment modalities. These gait observations include:

What is the foot doing?

What is the knee doing?

Is there abnormal pronation that is effecting knee motion that can be treated?

Is there abnormal supination effecting knee motion that can be treated?

Is the foot pronation linked with internal femoral rotation, or does the knee externally rotate at that time? (indicating opposite motions)

Is there varus thrust at the knee with excessive foot supination, or with excessive foot pronation? (causing wear of the medial knee compartment)

Does the foot pronate while the knee remains straight? (where torque stress can build up in the knee joint)

Is there limb dominance to the side of the worse knee pain? (Possible sign of short leg syndrome)

Is there excessive internal femoral rotation more than foot pronation? (Possible sign of weak external hip rotators)

Is the knee functioning too flexed, instead of straightening during midstance? (Possible sign of tight hamstrings)

Is the knee functioning too straight, instead of flexing during the heel contact phase? (Possible sign of weak quadriceps)

Let us take for example the patient who functions with the knees too flexed. It is typically caused be tight hamstrings (I am in that club!!) Here is a discussion on developing a good hamstring stretching program.

Hamstrings tightness is very common to athletes. Stretching of the hamstrings is one of the 3 most important lower extremity stretches that should be done both before (to prevent injury) and after (to gain flexibility and relax muscles) exercise. The other 2 muscle/tendon groups crucial to stretch are achilles and quadriceps. I feel most stretching articles are too overwhelming with 5 plus exercises. I would rather you understand one well, before proceeding further. For this discussion, I am only going to talk about Lower Hamstring (not Upper) Stretching.

The photo above shows the basic lower hamstring stretch getting the muscle/tendon loose around the back of the knee. The patients are told to place their heel on an elevated surface, like a chair or bench, where they feel no tension placing it there (the ballerina is showing off as usual). The knee should be held straight and the toes straight upwards. The patient should not attempt to touch their toes which places too much stress on the back. It is emphasized to the patient to lean forward over the leg being stretched feeling the bend at the hip joint, not the back. Imagine the back as completely straight. Lean forward over the leg until you feel tension behind the knee. It is very important since you are standing on one leg to feel very stable. Be near a wall or table that you can hold on with your arms if needed to gain stability. Do not make this into a balancing exercise.

Once you feel a great stretch, hold the stretch for 30 to 60 seconds (I love 5 to 8 deep breathes to get oxygen into the stretch. With every exhale, go slightly deeper into the stretch). There should never be pain with stretching either during or after. Pain during stretching will always mean 2 hours later you are tighter than when you started. Pain after stretching means you stretched too hard and next time stretch easier.

When stretching both legs, I like to alternate sides. The three stretch variations for the lower hamstring is all based on the big toe position. Let us discuss the right side, and I will leave it up to you to do the opposite for the left side. With the big toe at 12 o'clock, lean forward over the leg until you feel the pull of the hamstring behind the knee. Hold this painfree stretch for 30 to 60 seconds, or 8 deep breathes. Then do the left side. The second stretch for the right side is with the big toe at/near 9 o'clock. This gets a greater stretch on the medial hamstrings (semi-tendinosis and semi-membranosis). Then do the left side. The third stretch for the right side is with the big toe near 3 o'clock. This gets a greater stretch on the lateral hamstrings (biceps femoris, long and short heads).

You may be very surprised that one of the three stretches gets the sore muscle/tendon better than the other two. If so, do one more stretch to this variation for 8 more deep breathes, or go back it that stretch alone several times a day.

The photo illustration above shows the upper hamstring stretch. It is so important to stretch both the upper and lower hamstrings. This athlete is quite limber, so most of my patients will put their foot up on a wall to hold it for 30 to 60 seconds. It is okay to have your knee slightly bent. You should feel it high up on your thigh.

Probably the most common knee complaint that a podiatrist

will be called into treatment involves the kneecap.

Also called Chondromalacia Patellae, Patello Femoral Dysfunction, Quadriceps Insufficiency, Patello Femoral Insufficiency, Patellar Subluxation Syndrome, etc, etc, etc...

Associated with Excessive Internal Patellar Rotation or Position produced or aggravated by the internal talar rotation with foot pronation illustrated by the young women with her right knee below

-

All patients with Patello-Femoral Dysfunction should be treated with core strengthening especially external hip rotators, Quadriceps strengthening especially VMO with short arc single leg press and quad sets, and

- Vastus Lateralis Quad Stretching, Knee Brace to better patellar tracking, and foot stability with orthotic devices, stability shoes, and power lacing.

|

| Bauerfiend GenuTrain Knee Brace for Patellar Tracking Issues |

Here is some advice I emailed a patient inquiring about knee pain and flat feet:

Dear Dr Blake:

I am in a conundrum. Spend out of pocket to see a podiatrist or spend out of pocket to see a PT.I am Flat footed.

In 1990, my right knee hyper-bent with 150 lbs of backpack weighing me down with my right foot stuck in snow as the left foot slipped downward.

Current symptoms:

- Clicking knee cap

- Kneeling on carpet, great pain until the knee cap pops into place from pressure upwards

- Grinding knee upon flexing

- Pain on the inside of the rt knee and lower left quandrant of patella

- Pain and tightness from right side of knee up to the hip

- Pain behind my knee at the back (anterior)

- Extreme pain in knee and hip when rising up from a kneeling position

- Pain and tightness on the inside of my thigh at the knee

- Feeling of being swollen in the knee itself

- Walking in running shoes with support is OK at best

- Walking in dress type shoes with no support results in pain after 25 yards or so

- When I use to take spin classes, the instructor noted an outward or inward? movement of my leg/knee and asked me to keep it straight, which I could not.

I have sat at a desk for 8hr/day for the last two years ~ the first desk job in my life and this may be part of the problem.

I am self pay ~ no health insurance.

What would the cost range be for a diagnosis by you, treatment and possibly orthotics?

How long would it take, should we work together, to know if your regiment for me is working?

At what point would it be wise to pony up for an MRI? Do I need one?

I am 53, and until recently, in good shape if not great shape. I need help!

Best always and Happy New Year!

Robert

Robert, Thank you for the email. This is definitely a question about timing of treatments when both can be very helpful.

With that much knee pain, you are really in the immobilization/anti-inflammatory phase. Orthotics would be part of a restrengthening/return to activity phase. The immobilization is any thing that creates a pain free environment, from braces, to shoes, to activity changes, and yes, to orthotics if that is what it takes.

I would tend to have a PT cool your knee down first, and then add orthotics when you are ready to increase your activity again. Orthotics can play a role when you are throwing everything into the treatment arena but the kitchen sink (an approach used with unlimited funding).Definitely, cool the knee down with PT and Icing. The icing for the knee must be 30 minutes 3 times a day. Yes, 30 minutes is normally needed to get deep into the knee. Try to stay away from anti-inflam meds since they can slow bone healing. Get an MRI, around $500 self pay, if your symptoms plateau (look at it one month at a time). Try to create a pain free environment over the next month, which may mean staying in your most stable shoes. You can also try Sole over the counter Arch Supports (get one of the soft athletic versions). These are easy to adjust.You have already established a relationship between your feet and knees, but see if you can get them calmed down, less fragile, over the next several months.

Wedging of Medial and Lateral Compartments

The knee joint has 3 compartments.The anterior compartment is the patello-femoral

joint, and then you have the medial and lateral compartments. All 3 of these compartments

can get degenerative changes where possible surgeries with joint replacements are

common place. Podiatrists are typically called into this arena to wedge the foot/shoes to off

weight the knee compartment that is initially compromised. In the US, it is typically the

medial compartment, and in Asia, the lateral compartment with more knee flexion as part of

that culture. It is amazing how difficult it is to predict how effective foot wedging is on these

compartments, especially the medial side.

Podiatrists are taught to invert the wedge when the foot pronates excessively for medial

compartment disease, orthopods do the opposite. If the foot is supinated or neutral, then

both specialities valgus wedge the foot to help the knee. Both specialities do the same

varus wedging for the less common lateral compartment disease.

As a podiatrist, I team up with orthopedists to treat many knee conditions. One of the most gratifying is the treatment of lateral knee compartment disease. In attempt to avoid complete or partial knee replacements, I am asked to varus or medial wedge them to open up the lateral joint line. I can not tell you how successful it is, but I have many very happy patients. The treatments are always teamed with a variety of other treatments including synthetic cartilage injections, knee braces, knee strengthening, shoes selection, icing, and some cortisone shots.

As a podiatrist, I team up with orthopedists to treat many knee conditions. One of the most gratifying is the treatment of lateral knee compartment disease. In attempt to avoid complete or partial knee replacements, I am asked to varus or medial wedge them to open up the lateral joint line. I can not tell you how successful it is, but I have many very happy patients. The treatments are always teamed with a variety of other treatments including synthetic cartilage injections, knee braces, knee strengthening, shoes selection, icing, and some cortisone shots.

Ilio-Tibial Band Syndrome:

Women tend to get pain at the hip due to their wider pelvis, men at the knee.

Ilio-tibial Band Syndrome is almost exclusively a repetitive stress syndrome caused by running.

Excessive Pronation causes the ilio-tibial band to rub across the lateral femoral epicondyle at the knee, or greater trochanter at the hip.

Excessive Supination strains the band as it attempts to stabilize the lateral aspect of the hip and knee from the varus stress.

A short leg syndrome can commonly cause iliotibial band syndrome as the band attempts with every step to straighten the legs (to no avail).

Treatment includes correcting the biomechanics, icing several times a day, strengthening the hip abductors (core in general), and stretching the IT Band alot. I especially love the lateral wall stretch and the use of the ethafoam roller on the IT Band.

|

| A patient with classic limb dominance to the left suggestive of short leg syndrome. It could also be excessive supination on the left only throwing the hip laterally. The IT Band can get very unhappy as it attempts to constantly stabilize the lateral hip and knee. |

Pes Anserinus Strain is another running related injury.

The illustration above shows this very unique structure on the front and inside of the knee (anterior and medial) that is designed to stabilize the knee at heel contact. I see this as a secondary help to the knee joint in high stress like running down hills when the quadriceps have to stabilize a force up to 10 times body weight. The Pes Anserinus is made up of 3 tendons conjointly attaching in the front of the knee. The 3 tendons are the Sartorius (hip flexor), Gracilis (adductor), and Semi-Tendinosis (hamstring). So the quadriceps are helped medially by the pes anserinus and laterally by the ilio-tibial band.

When Do We Begin To Save Our Joints?

Just saw Lynne several days ago. Lynne brought up the age old question at her young age of 59 "do I stop running now to save my knees for the future?" Her knees have some X-ray and MRI findings of wear and tear. Lynne has never had any pain. She did have an episode of knee swelling and sought medical advice. Age old probably sage advice is to stop running since it is the most stressful of her activities on her knees.Lynne is high level triathlete. Yet is it the best advice for Lynne? Does running chew up your knees and hips and ankles silently until you wake up one day and can not walk? What do we know about the Nutritional Theory of cartilage health? What protects joints? What breaks them down? So many questions to be individualized for each of us.

My bias for recommending to Lynne to keep running comes from 5 factors. #1 Joint Cartilage is feed from pressure created in the joint from activity (nutritional theory of cartilage health). #2 Pain is our friend and will normally tell us way before severe damage is created that we must start limiting certain activities. #3 Sports Medicine for podiatrists evolved from being able to get injured knee patients to run pain free when the medical establishment was telling them to stop running forever, and I come from that time period of the mid 1970s.. #4 I personally want to keep exercising until I am 100 and I will continue to find ways to exercise (my last 3 orthopedic injuries found me at odds with surgeons wanting to cut, and I was able to successfully rehab each one, and am back playing full court basketball painfree). #5 When you break away from generalizations like stopping running to avoid knee wear and tear, you must own your knee more directly and do positive things daily for it.

So, Lynne had been running for 40 years, never had knee pain, did get swelling and her images showed classic wear and tear of a 59 year old. She did not have the knee joints of a 90 year old, so all the running she has done has not been bad for her knees. There was a famous study from Sweden or Norway (way up there) in the 1970s. Twelve 90 year olds who had died had there hip joints examined. All 12 never had hip pain. 6 of the 12 were very active their whole lives. 6 of the 12 were very inactive their whole lives. Guess who had the hip joint cartilage of 20 year olds--yes, the active group. The 6 individuals who had been inactive had hip joints of 90 years old (and not a day older). This study helped secure the global recognition that the cartilage in our joints needed pressure to drive the synovial fluid into the cartilage (a form of forced feeding).

Lynne stopped running to save her knees, but may be actually speeding their demise. Lynne can sure be smarter and try not to run down hill frequently where the force that your knee must absorb is up to 10 times body weight. And Lynne can get her knees strong with daily quad sets, straight leg raises, and short arc quad leg presses. Since most of her problem with wear and tear is behind the knee cap, and the load on the knee cap increases dramatically over a 45 degree knee bend, Lynne should do her activities and exercises in a 0 to 45 degree flexion range. Running is perfect for that, some parts of biking may not be. Let pain be your guide. Lynne should ice her knees with swelling or pain after activities, she should wear a knee brace (I love the Bauerfiend GenuTrain for this problem) when she runs to see if it helps. She could also learn the many ways of taping her knee like McConnell Taping. She should take glucosamine daily. And lastly, Lynne should listen to her body and get back out there, and not listen to general rules that may not apply to her. And as Sue Sylvester on Glee says: And that is how I C it!