Ankle Joint

Dorsiflexion Non-Weight Bearing with Subtalar

Neutral

The following is an excerpt from Book 2 of Practical Biomechanics for the Podiatrist

https://store.bookbaby.com/book/practical-biomechanics-for-the-podiatrist1

This is used for Pronation Syndrome, Tight

Muscles, and Weak Muscles. When

pronation is more than expected it could be coming from an equinus source. And,

if you understand the force length curve of the achilles, both the tighter and

the looser the achilles becomes, the weaker it gets. This is my second most

important test.

Here are the landmarks from head of

the fibula through the lateral malleolus (stable arm) and then along the

lateral side of the fifth metatarsal

Ankle joint dorsiflexion with the knee

extended and flexed will tell us a lot about the tightness or over flexibility

of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscles. A tight tendon and an over

flexible tendon are both weak for different physiological reasons concerning

their actin and myosin fibrils. These are the two muscles that make up the

achilles tendon, the strongest and most powerful and possibly the most

influential tendon in the body (definitely influencing the knee, ankle and the

entire foot). Tightness and over flexibility can have severe effects on the

knee, ankle, arch, and metatarsals. They directly affect the ankle and knee

joint (gastrocnemius crosses the knee), but indirectly affect every structure

in the foot. Being able to measure the overall tension in the achilles, and

seeing how it correlates to the normal Achilles force-length curve, is a very

powerful help in so many injuries including all Achilles problems, shin

splints, all ankle problems, all calf problems, all foot problems, etc. It is

probably influential in most lower extremity injuries to at least some degree when

either too tight or too loose.

Achilles’ tendon flexibility measurement

(called ankle joint dorsiflexion) is done along the lateral side of the foot

and leg. One arm of a measuring device (called goniometers or tractographs) is

aligned straight through the lateral plantar foot and the fifth metatarsal

head, and one arm is aligned through the lateral malleolus to the head of the

fibula. You can also attempt to separate the rearfoot from the forefoot for

forefoot equinus evaluations. You then grab the foot and slightly supinate the

subtalar joint by putting medial and upwards pressure on the first metatarsal.

You must maintain that subtalar joint position while you ask the patient to

help you pull the foot into a more flexed ankle position. Ideally, as the

patient pulls their foot up with a stable leg, the angle created for the

gastrocnemius tightness (knee extended) is 10-12 degrees, and for the soleus

tightness (knee flexed) is 15-18 degrees. In my travels, I have found some

doctors who supinate more than this so will get a normal flexibility of 0-5

degrees. I have also found those who allow the subtalar joint to pronate while

measuring and they will get increased range of motion and less equinus patients

(this is inherent in the Standing Lunge test discussed later). I believe if you

practice this technique on 10 individuals, the average should be 10 degrees

with the knee extended and 15 degrees with the knee flexed, with some being

tighter and some being looser. If your average is less or more than this by

many degrees, you should go back and read through the steps listed above and

review the upcoming photos.

What does this mean? When we take a step,

for smooth transfer of weight forward, our ankles must dorsiflex in the mid

stance of gait. At the middle of midstance, our body’s weight is directly over

our foot, and our ankle joint is at neutral position or 0 degrees dorsiflexed.

As our weight goes forward from here, just as we lift our heels off the ground,

the ankle has now dorsiflexed 10 degrees with the knee relatively straight. As

the heel lifts off the ground, we begin the propulsive phase of gait, with

ankle plantar flexion and knee flexion preparing to lift the foot and toes off

the ground. So, for a smooth gait, the ankle should bend 10 degrees at a time

when the knee is fairly straight (and there is tension on the gastrocnemius).

This is the definition of normal ankle joint dorsiflexion that has been taught

for decades in podiatry schools and that I use in my practice. When the knee is

straight (probably within the last 10-15 degrees toward extension), there is

tension on the gastrocnemius, and if we have less than 10 degrees, we have an

equinus deformity, and if we have more than 12 degrees, we are over flexible.

The measurements are accurate within 2 degrees, and change 2-3 degrees from

morning to night into a more flexible state. It is my experience that finding

ankle equinus (tight achilles) will normally have some effect on gait findings

and symptom relief if reversed.

Our landmarks of the plantar surface

of the calcaneus and fifth metatarsal to the bisection of both the lateral

malleolus and head of the fibula

Remember to slightly load the medial

column to prevent subtalar pronation before dorsiflexing the ankle (you will

feel patients trying to pronate to get more degrees and you must resist that

attempt)

Always watch to make sure the knee

does not hyper-extend with ankle dorsiflexion, especially in known cases of

equinus that you are trying to stretch out

A Goniometer or Tractograph is used

You must have good visual on our

four landmarks while you dorsiflex the ankle to resistance and prevent subtalar

pronation (this takes students awhile to learn as hand positioning is

everything)

Your Eyes should be at the level of

the measurement (any measurement) that you are performing. Here you can see

that all landmarks are easily visible to me.

After the straight knee

gastrocnemius evaluation, you will bend the knee and begin to measure for

Soleus flexibility

The Soleus is measured with the Same

Landmarks (my head bent only for the photo)

Lateral Foot to Lateral Leg again

making sure the subtalar joint does not pronate by gently loading the medial

aspect of the foot

Practical

Biomechanics Question #126: The reliability of the ankle joint dorsiflexion

test comes from biomechanical experts discovering that the manifestations of

equinus seen in gait (as listed in Chapter 3) correlated to this subtalar

neutral measurement. In most of my equinus patients, I see an improvement in

gait and/or symptoms if I can stretch them out. If you measure equinus, what

gait findings may be present in your patient?

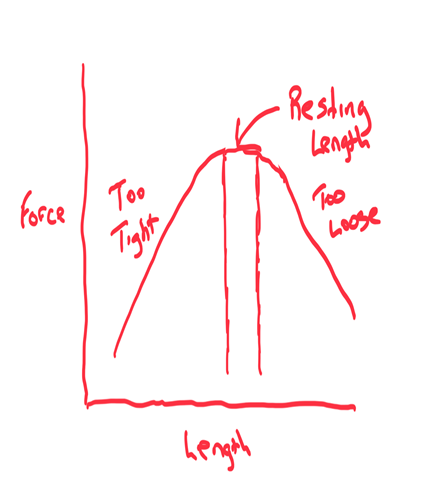

Force Length or Length Tension Curve

This is a perfect time to discuss the

force-length (or length tension) curve of tendons where the normal lower

extremity tendons (Achilles, quadriceps, and hamstrings) have been extensively

measured. Force is the vertical axis and Length of the Tendon is the horizontal

axis of this curve. The normal length of a tendon, where it is considered not

tight or not too flexible, is called the Resting Length, or Normal

Physiological Length. If the gastrocnemius is normal at ankle joint

dorsiflexion of 10-12 degrees, it means it is too tight at less than 10

degrees, and it means it is too loose at greater than 12 degrees. The same is

true for the soleus at 15-18 degrees normal, under 15 tight to some degree, and

over 18 loose to some degree. The Force Length curve argues that away from its

Normal Physiological Length that any tendon becomes weaker. When a tendon is

tighter than it should be, aka muscle-bound, the actin and myosin fibrils are

too bound up, producing less of a neuro-muscular charge, and therefore less of

a powerful contraction. The tighter a tendon is away from its normal, the

weaker it becomes. I have found this so true and it has helped me manage many

injuries with this knowledge. The same is true when the tendon is looser than

normal, it becomes weaker, or more stretched out. Here the actin and myosin

fibrils are not in as close contact with each other, thus less of a

neuro-muscular charge, thus weaker in function.

I am sure as I treat patients that we do

not have to be literal to the exact degree. I have seen so many patients only

manage to length or shorten a tendon half of what I want, and get great results

in the symptoms. If I think it is a problem, I measure patients monthly and

check these results against the changes in their symptoms. Symptoms and tendon

abnormalities measured by this examination go hand in hand.

Practical

Biomechanics Question #127: Every muscle/tendon complex has a certain inherent

tension that makes it function normally and powerfully. What is this called?

There are so many examples of how this is

important, but I will just mention one here. A patient presented to the office

with 2 years of chronic Achilles tendinitis. Previous MRIs and ultrasound had

not found any problem but perhaps some inflammation along the achilles. The

previous treatment had been for Achilles stretching three times a day, orthotic

devices for heel stability, icing, some physical therapy for flexibility,

strength, and anti-inflammatory, and when there was no improvement, some

acupuncture and a surgical opinion to lengthen the tight tendon. Occam's Razor

is that Achilles pain is usually from a tight achilles tendon, and the

treatment was to stretch it out to normal length, so the unsuccessful treatment

was not out of the ordinary. So, why was he not improving?

The Achilles’ tendon definitely had slight

swelling, but not like the fusiform swelling in the zone of ischemia of

tendinosis. The patient could not do 25 single heel raises (my gold standard of

Achilles strength), in fact even one single leg heel raise was both difficult

to do and painful. At this point, you can not be sure if the inability to do a

single heel raise was due to just pain, weakness, or both. However, when I

measured his ankle joint dorsiflexion, I found 29 degrees with the knee

extended, and 34 degrees with the knee flexed. Who knows what the flexibility

was when he started, but his stretching 3 or more times a day for 2 years had

probably gone in the wrong direction. He mentioned that a PT had measured him

at some point, and did not find any tightness, but proceeded to continue

achilles protocol to stretch him out. She was the only one to measure him, and

sadly the doctor who was going to lengthen his tendon had not measured him

(presumably going to do surgery on an assumption not fact).

When I told him I want heel lifts and

shoes with heel elevation nonstop for the next month with no stretching, I

could tell he really did not believe me. I also wanted pain free 2 positional

Achilles strengthening (called double leg heel raises), and it would take a

while to do a single leg heel raise pain free, but two positional was fine to

start and build up to 100 each evening. If he feels tight (weak strained

muscles with some inflammation can feel very tight), which alot of these

patients do, I allow calf massage. After the first month, he was beginning to

feel symptomatically better, and his measurements had reduced to 22 and 29

respectively. By the end of the next month, he had almost no pain, and his

measurements were 17 and 26 respectively. He passed the 30 minutes of pain-free

fast walking test at 2 and ½ months, so I started him on a walk-run program as

part of his Return to Activity program with no speed or hills initially. By the

end of the fourth month, he was running 30 minutes pain-free, and his

measurements were 14 and 24. I told him he was still too over flexible, and not

out of the woods. I discouraged any form of stretching for another couple

months and made sure he warmed up well walking or on a stationary bike before

running. The best I ever measured him in the next few visits, until lost to

followup, was 13 and 22.

Just a quick note on strengthening in cases

like this. His double, and then single, heel raises were done in the evening

only. This will be covered in Chapter 11 Book 3. You do not want the fatigue

from strengthening to cause him symptoms. So, build up strength, go to bed, and

the next day you will be a little stronger. Also, in case the strengthening

irritated the tendon somewhat, there was time to ice the achilles afterwards if

need be.

Practical

Biomechanics Question #128: If an achilles tendon gets over-stretched, what

might you see in gait?

I also want to discuss ankle joint

dorsiflexion measurement weight bearing.

Lunge Test is a Weight Bearing

Version of Ankle Joint Dorsiflexion Flexibility (Soleus version shown here)

This

examination technique will give you more force than the prone method which

definitely means it will give you less equinus in terms of percentage of

patients. The opposite is true with the non-weight bearing technique that holds

the subtalar joint maximally supinated during the examination. This will

definitely give you more patients below the normal 10-12 degrees with the knee

extended therefore considered equinus patients. I can only say that there is

validity to all three techniques for different reasons. The weight bearing

technique (and the maximally supinated non weight bearing technique) uses the

same measurement of fifth metatarsal to plantar calcaneus, and lateral

malleolus to head of the fibula. There is an attempt at holding the patient in

subtalar neutral, even better if your orthotic devices approach that position

so the patient can just stand on their orthotic devices for the Lunge Test. The

weight bearing loading of the foot stretches the plantar tissue and can allow

the front of the ankle to slide forward even when the subtalar joint is

stationary near neutral. I would love to see if the criteria of positive gait

findings for equinus matches these patients. In teaching examination techniques

for years, I find that the most important thing is that each practitioner

measures with one technique over and over again, and therefore will develop

reliability with these tests. If the patient demonstrates equinus in gait, and

the test that you perform documents equinus, there is no reason to change. We

are using our measurements to find clues to successfully treat our patients.

The simple Lunge test deserves further

discussion. The left foot is 2 feet or so in front of the right foot, same base

of gait, and the patient flexes both knees just to the point of the heels

wanting to come off the ground. The angle of the tibia to the ground is

measured with 35-38 degrees being normal. Over 38 degrees and the patient is

considered hypermobile, under 35 degrees the patient is considered tight. I use

an app (Bubble Level XL) on my iphone to measure, and then I can follow them

through their stretching or strengthening program. I look at this as a

screening tool, since you really should get an average of 5 tests to be

reliable, and this test does not have a reliable fixed point that you are

measuring against since both the foot is moving and the tibia is moving (unlike

the fixed tibia on the moving foot with my preferred subtalar neutral non

weight bearing test). The examiner has to find a tool he can use that will show

change (so it has to be reproducible to the examiner). The same test can be

done with the knees straight to measure gastrocnemius flexibility.

Bubble Level XL app noting 45

degrees of Soleus Flexibility (Knees Bent)

Practical

Biomechanics Question #129: Which 4 achilles flexibility tests for the achilles

tendon are utilized in the profession, and what is the criteria for reliability

utilizing gait patterns?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you very much for leaving a comment. Due to my time restraints, some comments may not be answered.I will answer questions that I feel will help the community as a whole.. I can only answer medical questions in a general form. No specific answers can be given. Please consult a podiatrist, therapist, orthopedist, or sports medicine physician in your area for specific questions.